From Motorbikes to Satellites: Senegal’s New AI Approach to Forest Protection

From the giant baobab trees, wetlands and mangrove in the north to the green, tropical vegetation in the south, Senegal is home to a wide variety of forest ecosystems. However, a worrying trend is disrupting this habitat: forests are steadily dwindling due to forest fires, illegal logging, and other human activities.

This loss of forest cover reduces the amount of carbon stored in trees and soils—also known as carbon sinks—thereby releasing more CO₂ into the atmosphere and contributing to global warming. Since measurements began in 2007, the amount of carbon stored in Senegal’s forests has been steadily declining, with national authorities estimating a loss of 40,000 hectares of forest every year.

Senegal’s forest authority, the Direction des Eaux et Forêts (DEFCCS), has been in the forefront of the preservation of this ecosystem. Lieutenant Mamadou Diop (Kolda region) and his colleagues collaborate with local communities across the country – such as Yassin Madina, – to reforest burned areas, raise awareness about forest protection, and manage communal forests sustainably for firewood harvesting or agroforestry. To identify areas at risk, such as those threatened by wildfires, Lieutenant Diop benefits from remote sensing technology available on his computer and smartphone.

When it comes to forest management, accurate and up-to-date national carbon sink maps would add value. Such maps would enable more effective targeting of interventions and help prioritise forest areas most in need of protection. Yet their development depends heavily on extensive, reliable and timely field data.

In Senegal, much of this data—such as tree height, trunk circumference, and species type—is still collected manually by rangers who travel deep into the forest, often on motorbikes, to record observations and check for burn marks. This painstaking work is essential for estimating biomass and carbon sinks, yet it is extremely time-consuming and resource intensive.

The solution: AI-based High Carbon Stock Approach

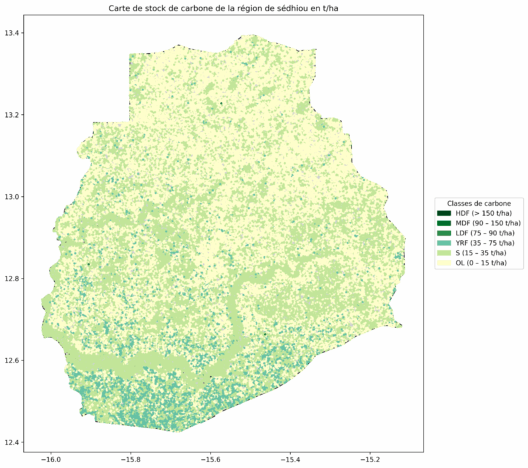

Together with data354 and the Ministry of Environment and Ecological Transition (METE), the Carbon Lense Senegal project, implemented by GIZ and supported by the BMZ– funded initiatives Data Economy and FAIR Forward, is working to scale the High Carbon Stock Approach (HCSA) – first piloted by FAIR Forward in Indonesia, India, and Ivory Coast – to Senegal. This methodology uses artificial intelligence (AI) to generate carbon maps, combining open satellite imagery with locally collected forest inventory data.

An automated carbon map would greatly simplify our forest management work. Currently, we still travel up to 300-kilometres by motorbike per week to collect data.

Leutnant Mamadou Diop, Kolda region, Senegal

The AI-based High Carbon Stock Approach enables the creation of carbon maps by combining open satellite data with locally collected forest inventory data. By training an AI model on biomass data from West African tree species, it could accurately estimate how much carbon is stored in Senegal’s forests. At present, however, very little scientific data exists on the carbon content of these species. To address this, the project is working with the University of Ziguinchor (Senegal) to generate new scientific knowledge. This solution will provide a stronger foundation for accurate carbon measurement, sustainable forest management, and evidence-based climate policy.

Local communities, whose lives are closely tied to the forests, also see a need for action. Therefore, local rangers from the DEFCCS will be directly involved in this process, contributing their knowledge of local ecosystems while supporting data collection.

A first joint field mission tested the forest inventory protocol used by the DEFCCS under real conditions. The mission was carried out in the Middle Casamance (Sédhiou region, Senegal), a forest-rich area that provided an ideal setting for the data collection protocol calibration. The next step is to extend the approach to other ecological zones in Senegal, ultimately creating a national biomass map.

The forests are changing, but we need them for agroforestry. Forest fires pose an additional challenge.

Babacar Mané, Community Chief, Yassin Madina

The new possibilities facilitated by this initiative teach us an important lesson: digital technologies, including AI, can become useful tools to bridge both biodiversity conservation and climate objectives. When combined with local knowledge, tech-enabled solutions can be replicated and adapted to different regional needs – as just presented at the UNFCCC TEC’s AI for Climate Action Forum 2025 in Tanzania.

Bringing together partners from different sectors – digital, forestry, and climate – is crucial to guarantee that solutions are shaped by different perspective and account for specific needs. Moreover, the High Carbon Stock Approach’s outputs will directly serve Senegal’s reporting of nationally determined contributions (NDCs) under the Paris Agreement, adding to the momentum for transformation this project has set in motion.