Fair platform work—Gig Economy

The mobile phone lights up, one click, a new job: delivery and driving services have transformed the online labour market. Offering flexible jobs, the gig economy attracts women and young people in particular, but often lacks social protection, fair pay and transparent management. The Gig Economy initiative aims to address these deficits, for example by evaluating job platforms and advising operators on how to improve working conditions or inform job seekers of their rights. As a result, millions of people have already benefited from higher minimum standards.

million people worldwide work on digital platforms.

are women relying on online gig work as their main source of income.

of gig workers have the right to unionise and co-determine.

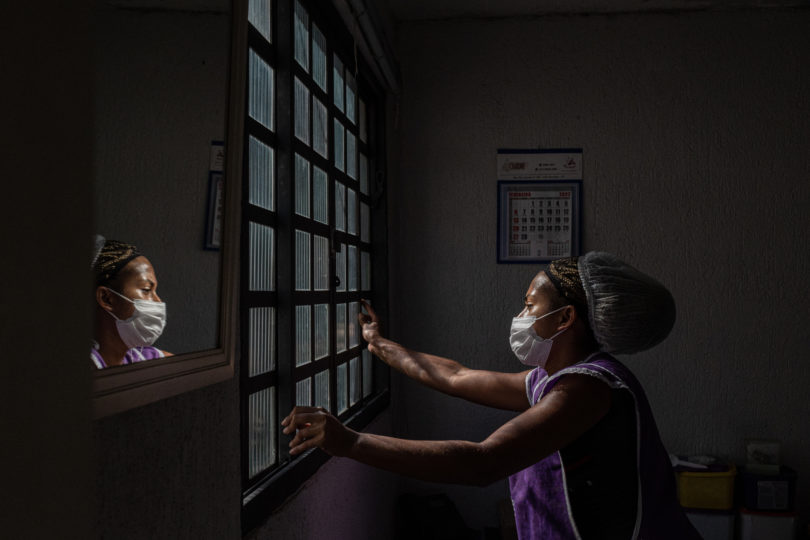

Women in Kenya’s gig economy are fighting discrimination—including on digital platforms. Cowan Koduk uses the knowledge she has gained from a mentoring programme to teach other women about fair work and safety, and has built a strong community for greater equality in the gig economy.

Our approach and goal

The aim of the Gig Economy initiative is to create the necessary conditions for fair work in the gig economy at the level of

- workers

- platforms and

- other key stakeholders from politics, business and civil society.

With its holistic approach it seeks to strike a balance between enabling new and equitable employment opportunities and minimising existing challenges.

The initiative offers training and guidance for workers, supports the scale-up of an evaluation mechanism for the fairness of platforms and advises platforms on how to improve their working conditions. The initiative also raises awareness among policy stakeholders for the potentials and risks of the gig economy and existing regulatory gaps.

Brazil’s gig workers

Jessica, Marcelo and Juliana are three of more than 600,000 Brazilian workers who take orders daily through digital labour platforms. Mostly without fair pay, labour protection or the right to organise collectively with other workers—effectively excluded from the protection of Brazilian labour law. We have accompanied them in their everyday life.

open photo reportageOur activities

-

The Gig Economy initiative has developed a number of online, data-driven tools and is implementing capacity measures in form of training courses for gig workers, for which you can enroll here. The aim is to help them better navigate the gig economy, find decent jobs or work outside digital labour platforms. These human-centered learning opportunities raise gig workers’ awareness on in-demand skills, their digital and work rights. So far, more than 20,000 workers and their allies have participated in these programmes, improving their understanding of needs, challenges, and skills gaps.

These eLearning, gig talks and hybrid training formats offer workers a basic orientation to platform work and fair working conditions. In addition, these courses provide information on gender and resilience, as well as important financial, social, and digital skills in the gig economy. With some modules targeting specific sectors of platform work such as online freelancers and courier services. The accumulated learnings from these trainings have been captured in two Toolkits, designed to assist agencies in replicating either a Mentorship & Peer Learning Programme or an Online Freelancer Training in their own local context and setting.

The training courses improve their knowledge of their own rights and inform on job and career opportunities. They enable them to train and adapt quickly to the dynamic labour market, leading to better working conditions and a higher income for gig workers.

For example:

- To provide workers with insights on the value of micro-credentials for their career development and advancement, an information tool on the value of micro-credentials has been launched.

- To provide workers with up-to-date and verified information on current costs of a gig, the Living Tariff Calculator has been launched in Kenya, Pakistan, Indonesia and India. The tool is based on the living wages database of the WageIndicator foundation and offers useful insights for workers, policy stakeholders and intermediary organisations.

- The ‘UpSkill’ tool is being piloted globally. The aim is to identify desirable skills according to real time platform data in order to provide informed future skill development recommendations.

The Initiative has a strong focus on gender equality and maximising the potential of women workers. Special initiatives such as mentorship and peer-learning programme have been implemented to empower women workers and support their personal and professional growth.

A range of other training formats and training of trainers are being organised to achieve sustainable and long-term impact through intermediary organisations such as worker unions and allied organisations, labor institutes, employment agencies and community-based organisations.

Women Leading Digital—the podcast

Even though women make up half of the world’s population, men clearly outnumber women in the digital world. In 2023, 224 million more men used the internet than women—almost three times the German population. Without the internet, women lack access to information, education, networks, job platforms, financial products and services. This situation is called the digital divide and it is widening.

In the podcast “Women leading Digital”, we interview brilliant women who are developing new technology and shaping digital change worldwide—despite the challenges they face. We talk to them about the experience of working in a traditionally male-dominated field and what solutions they are developing to bridge the digital divide between genders.

Publications

Further information

-

Learn to navigate the gig economy

E-learning courses for gig workers to maximise their potential and support moving in and out of the gig economy.

Overview of e-learning offers -

Registration page

for policystakeholder course: Understand the potentials and risks of digital labour platforms.

register here -

Re:publica 2023 : Click, Hire, Fire Improving the Global Reality and Future of Platform Work

with opening address from Svenja Schulze Minister for Economic Cooperation and Development.

Watch the recording -

Informational tool on the value of micro-credentials

The training courses can lead to better working conditions and a higher income for gig workers.

Website -

Living Tariff Tool

for platform workers calculating the minimum income needed to meet a living wage according to local conditions.

Website -

Fairwork Summit

Fair Work on Digital Platforms.

Watch the recording -

Multi-Stakeholder-Dialogue

Policies towards fairer online gig work.

Watch the recording -

Interactive game 'A day in the life of a platform worker'

Experience a day as a rideshare driver.

Play the Game