© freestocks / unsplash

The concept of “decent work” is a central idea promoted by the International Labour Organization (ILO), a specialized agency of the United Nations. The concept emphasizes the importance of work as a means of achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and improving the quality of life for individuals and communities. Decent work refers to not only the actual conditions of the work but the long-term meaning this work has for individual development.

The growth of online platform-based work forces us to consider how the principles of decent work can also encompass the plethora of new jobs stemming from the global digital transformation. Particularly, how the digital transformation can reduce and not exacerbate the current divide between Global South and North countries. This article by Uma Rani (ILO), Abas Muhind (Thunderbird School of Global Management), Grace Muraya (University of Nairobi) and Nora Gobel (ILO) of the International Labour Organisation, explores how universal the idea of decent work is and what we should consider when assessing the sustainability of microwork in the global south.

Microtaskers are individuals who undertake small, discrete tasks that typically take only a few seconds or minutes to complete. These simple and repetitive tasks are of a routine nature and require human cognition, without the need of specialized skills. They are usually parts of larger projects or workflows, that are fragmented and outsourced on online microtask platforms or through impact sourcing companies, often referred to as Business Process Outsourcing (BPO) companies, predominantly in developing economies.

The tasks performed by microtaskers can be classified into two main categories:

- The first category relates to artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning, including tasks like content moderation, data collection, categorization, image annotation, translation, transcription, audio and image recording.

- The second category relates to tasks involved in promoting products, such as search engine optimization, content access, market research, and reviews.

Some of these tasks may have the potential to be automated in the future, while others are likely to remain dependent on human judgement or input. Despite the ongoing discourse about automation in the AI industry, there is a growing reliance on invisible labour on microtask platforms and BPO companies for the development of AI. These workers play a vital role in tasks like preparation, verification, and development of AI, as demonstrated by OpenAI’s ChatGPT, which utilized Kenyan workers from the BPO company Sama to address toxicity issues, including addressing violent, sexist, or racist responses. Similarly, the automotive industry relies on these workers to annotate vast amounts of data for self-driving cars, which would be costly if done in-house.

The microtask workers not only remain largely invisible but also work under precarious working conditions. As many of them struggle to find adequate employment opportunities in the local labour market, the typically young and educated workers rely on this type of work yet find it challenging to secure a sustainable livelihood from it.

While typically both men and women perform these tasks, there is an uneven gender balance according to a global survey of microtask workers, with one in four workers being women in developing economies. In a country survey of 260 workers in Kenya, however, more than half of the respondents were women. The findings of both surveys indicate that the educational profile of these microtaskers is remarkable. Approximately 70 percent of the workers in developing economies have at least a bachelor’s or post-graduate degree, and 57 percent of them specialize in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM). In Kenya, about half of the surveyed workers had a university degree, with nearly 40 percent specializing in STEM education. The engagement of such a highly educated workers in simple, repetitive tasks highlights a significant underutilization of their skills. While tasks related to AI and machine learning were prevalent among respondents in the global survey, these were even more common in Kenya as almost all the respondents reported engaging in such tasks.

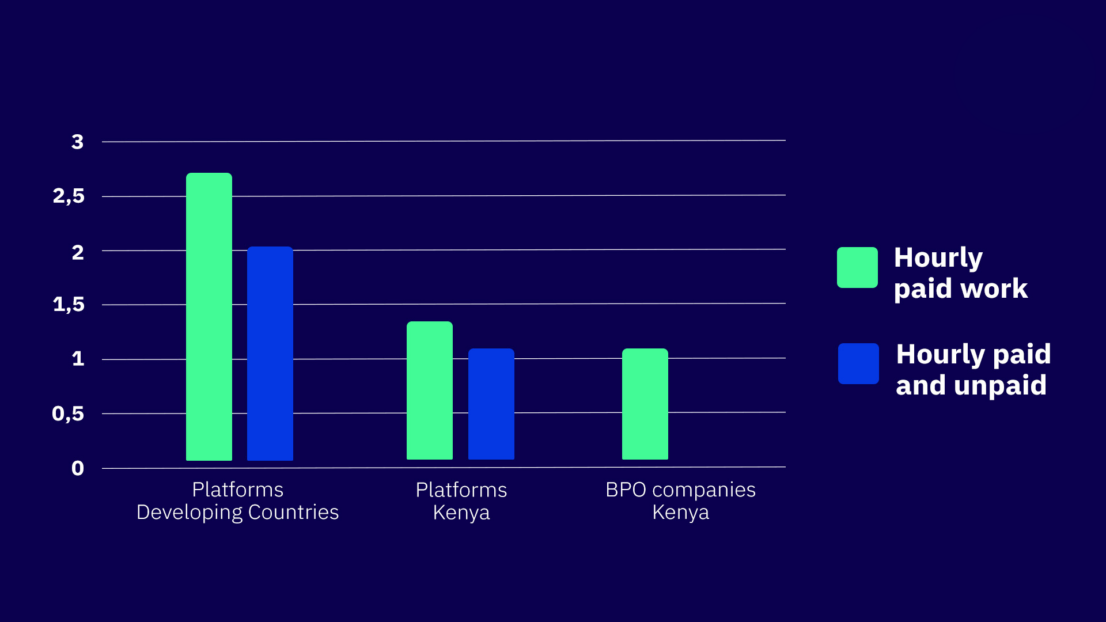

In Kenya, while microtask work serves as the primary income source for the majority of microtaskers on platforms (67 percent) and at BPO companies (93 percent), the earnings are very low. In developing countries, their average hourly pay on platforms was as low as $2.8 in 2017, with Kenyan workers earning about a dollar ($1.3) in 2022. It is important to note that these hourly earnings further decrease when unpaid hours (such as searching for tasks, rejection of work, etc) are considered – to $2.1 in developing countries and $1.1 in Kenya. BPO workers reported comparable wages in Kenya, $1.1 per hour (see figure 1). Notably, while the median wage for BPO workers matched their average earnings, the median earnings for platform workers in Kenya were slightly lower at $0.8, suggesting that a significant number of workers earn below the average.

Furthermore, in Kenya, when looking at the total hourly earnings on microtask platforms (including paid and unpaid time), workers undertaking transcription tasks reported the highest hourly earnings ($1.1), while those undertaking content moderation reported the lowest pay per hour ($0.7). While there are clear variations in earnings across different tasks on platforms, the disparity is less pronounced in the BPO companies, with workers typically earning similar amounts regardless of the primary task they perform. Gender differences in pay exist in Kenya, with women earning more ($1.2) than men ($0.95) on microtask platforms, while the earnings are quite similar for men ($1.2) and women ($1.1) in the BPO companies. Despite low pay, nearly all the microtask workers wanted to do more work on platforms. However, about 80 per cent of the surveyed workers reported lack of available tasks as a constraint, which could be due to high competition on platforms as there is oversupply of labour.

Due to the pressure of earning a decent income with such low wages, workers on platforms do not have the flexibility to choose their working hours. In addition, they frequently encounter unfair rejection of their submitted tasks, leading them to work extended hours and even over the weekend, without corresponding pay. They typically do not have access to labour and social protection benefits, while BPO workers may receive such benefits based on their employment contracts.

Moreover, concerns about the low pay and psychosocial impacts of content moderation are particularly pronounced among BPO workers engaged in these tasks, which is well-documented. For instance, the previously mentioned case of training ChatGPT, which might enhance the productivity of highly skilled workers, highlights a trend where workers in the global south are utilized to address toxicity issues. Times magazine recently exposed the low pay and traumatic experiences of some of the content moderation workers, including breaches of confidentiality by some counsellors. This exploitative situation led workers to organize and take collective action. In response, key organizers faced termination, leading to the initiation of a legal case, Daniel Motaung v. Samasource Kenya EPZ Limited, Meta Platforms INC, Meta Platforms Ireland Ltd, which is still ongoing.

The rise in microtask opportunities in developing countries, particularly low-end AI and machine learning tasks performed by skilled workers, raises significant social and developmental concerns. As the survey results illustrate, these workers find themselves in precarious situations, struggling to earn adequate incomes and lacking essential benefits and protections. Many have invested substantial financial resources in their education with the hope of securing formal employment, only to end up undertaking these tasks due to limited job opportunities. The outsourcing of such tasks is also concerning as it poses a risk of underutilizing highly skilled and professionally certified workers in various fields, and potentially creating a sweatshop of digital labour in developing economies. Further, it can lead to a reduced labour share in income, workforce polarization, and increased income inequality.

This situation calls for a need to have a crucial debate about the nature of employment opportunities that should be generated in economies with a growing educated and skilled workforce. How do these tasks contribute to the advancement of the careers of highly qualified and skilled workers in the global south at an individual level? How do these tasks foster transformation in their societies and economies? This situation begs an important question about whether this transformation should be encouraged, or if the knowledge and skills of these workers could be harnessed to develop tools and technologies that benefit their societies and economies. Such considerations necessitate further reflection on policies and regulations that balance the need for ensuring labour and social protection as well as the creation of quality jobs for all.